Do you know the name Agnes Gwynne? Hmmm … not ringing any bells?

How about Miles Franklin, Henry Handel Richardson or Mary Grant Bruce? Ah, yes, a few nods of recognition, especially if you had to study Miles Franklin’s My Brilliant Career or Henry Handel Richardson’s The Getting of Wisdom at school, or if you are a reader of ‘a certain age’ who devoured Mary Grant Bruce’s Billabong books in your youth.

Agnes Gwynne, like Miles, ‘Henry’ (a pseudonym for Ethel) and Mary, is an Australian woman writer who published novels in the 1920s. Unlike the other three authors, Agnes’s books are out of print and almost completely forgotten. She receives a scant 100-word entry in the Oxford Companion to Australian Literature and is not mentioned at all in either the Australian Dictionary of Biography or the Australian Women’s Register.

Beginning on Baraba Baraba Land

Agnes Mary Gwynne, the third of four children, was born into a prosperous ‘pioneering’ family at Werai on the Edward River, downstream from Deniliquin, in 1862.

Reproduced under CC BY-SA 4.0.

In the early 1840s, Agnes’s father, Henry Gwynne, had been one of a quartet of white men who claimed Baraba Baraba land in what became known as the Riverina region. The quartet also included Ben Boyd, speculator, banker and blackbirder. Another was Henry Lewes – later to become Henry’s father-in-law and therefore Agnes’s grandfather – a man who relieved ‘the monotony of his pioneer life … by well fought battles with the blacks, who became more troublesome as the white men increased’ (‘A Tour to the South’).

Henry used an Aboriginal word, ‘werai’, meaning ‘look out’, to name the land on which he farmed.

Daughter of an Entrepreneurial Father

Henry had a taste for the new and the untried. In 1849, prior to his marriage to Agnes’s mother, he had spent some time in California where he ‘underwent all the experiences of the wild life of the early gold-field days’ (‘A Deniliquin Pioneer’). He seems to have been regularly on the lookout for a new adventure.

When Agnes was four years old, the family moved to the outskirts of Geelong, a shift possibly prompted by Henry’s health needs. At Werai, he had established a successful irrigation system to water the household’s fruit and vegetable plots, but ‘the miasma constantly rising about his garden’ created a ‘moist atmosphere’, ‘endangering the health of himself and his family’ (‘A Tour to the Riverine District’).

Henry now turned his attention to a new undertaking – the development of the coastal township of Lorne and, in particular, the construction of the Grand Pacific Hotel.

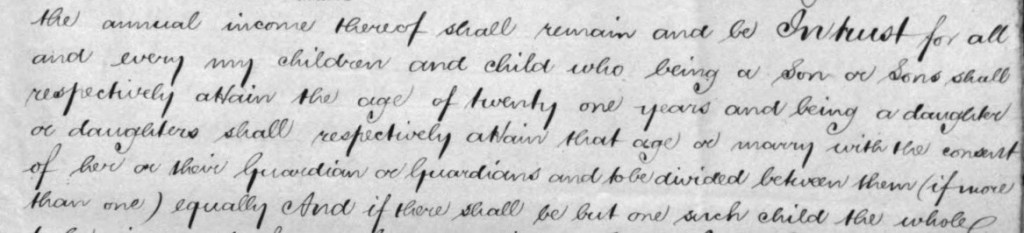

Henry Gwynne died when Agnes was in her late twenties; he left an estate valued at more than £14,000 (allowing for inflation, over AUD$2,000,000 in today’s terms). Agnes, her brother Charles, and sisters Grace and Alice received equal shares in the income derived from the estate. (A decade later, Charles and Agnes each also received £1,000 from the estate of their Uncle Francis, Henry’s brother.)

A Writing Career Takes Off at Lorne

Although Henry had attempted to sell the Grand Pacific Hotel in 1883, the popular Lorne establishment remained under the family’s control for decades to come. Agnes’s brother Charles took over proprietorship of the hotel after Henry’s death in 1890, and the remaining family members soon moved from Geelong to Lorne. (The hotel was eventually auctioned in 1922 following Charles’s death the previous year.)

During the 1890s, local newspapers list Agnes’s name (sometimes using the diminutive ‘Nessie’) as a singer at Lorne concerts. She sang solo and in a duet with the popular English tenor Charles Saunders at a concert to raise money for the building of All Saints’ Church, and she opened the programme at a fundraiser to aid the construction of walking tracks to the seaside town’s resorts.

Electoral rolls confirm Agnes’s residence in Lorne from 1903 to 1921, and it is during these first two decades of the 20th century that her literary career begins. The coastal strip stretching from Geelong to Portland would feature regularly in Agnes’s writing for decades to come.

Books and Themes

Between 1908 and 1935, Agnes Gwynne published two plays and five novels, the last of which, the historical romance High Dawn, was published posthumously. Her protagonists are generally wealthy, independently minded women.

Agnes’s first publication, for which she won first prize of £25 in the literature section of the Women’s Work Exhibition for a ‘play of three acts, scene laid in Australia’ (‘Women’s Work Exhibition’) was A Social Experiment. The play pits two men – one a fervent socialist, the other an avowed capitalist pastoralist – against each other; the main female character, Muriel Mannering, sees value in both perspectives. The juxtaposition of political ideologies recurs in two of Agnes’s novels, The Mistress of Windfells (1921) and The Mystery of Lakeside House (1925), and in her second play, The Capitalist.

Another recurring theme in Agnes’s books is the flow-on effect of a man’s bequest to a female relative via the stipulations of a will. In An Emergency Husband, the will decrees that the deceased’s niece, Gwendoline Vaughan, must marry within six months or the whole of a sizeable estate will be re-directed to distant relatives. Other women in Agnes’s fiction are less encumbered by the terms of a will: upon marrying, Muriel Mannering (A Social Experiment) uses a portion of the inheritance left to her by her father to cover the mortgage on her husband’s heavily indebted farm; Joan Fetherston (The Mistress of Windfells) is the sole heir to her father’s 13,000-acre sheep property.

A Puzzle

Given that Agnes spent most of her life living in, or on the edge of, towns and cities, I am curious about the credible depictions of sheep farming in Victoria’s Western District in several of her books. How did she gain such a detailed knowledge of the annual recruitment of shearers, the art of shearing, and the workings of woolsheds?

A possible answer lies with her wealthy brother-in-law Archibald Johnson, husband of Agnes’s younger sister, Alice. Agnes spent long periods with the Johnsons, even accompanying them on three extended journeys to England and, closer to home, on voyages to Java and Papua. In her later years, she lived a 10-minute walk from their residence, Toorak House (an impressive mansion that had previously housed Victoria’s colonial governors).

How is time spent with Alice and Archibald relevant?

Archibald Johnson owned the extensive and profitable Western District property, Chetwynd.

A property that ran …

sheep.

I shall write more on Agnes’s sheep-property settings another day.

Links and Sources

Agnes Gwynne’s books (note that although Agnes’s books are out of print, some are freely available online ):

- A Social Experiment: A Comedy. Melbourne: Lothian, 1908

- The Bathing-Man. London: John Lane, 1916

- The Mistress of Windfells. Melbourne: E. W. Cole, 1921

- The Mystery of Lakeside House. Melbourne: Robertson and Mullens, 1925

- An Emergency Husband. London: M. G. Maurice, [1928]

- The Capitalist: An Original Play in One Act. Melbourne: Frank Wilmot, 1931

- High Dawn. Melbourne: Robertson and Mullens, 1935

Red River Gums, Edward River Crossing, the Riverina, NSW. Photo by Margaret R Donald. Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Riverina regional history: Aboriginal Occupation

Quote about Henry Lewes from ‘A Tour to the South’, Australian Town and Country Journal, 1 June 1872, p. 17

Quote about Henry Gwynne’s experience in California from ‘A Deniliquin Pioneer’, Riverina Recorder, 20 August 1890, p. 2

Quote about Henry Gwynne’s irrigation system from ‘A Tour in the Riverine District’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 13 July 1865, p. 2

Grand Pacific Hotel and Jetty, Lorne, circa 1876-94, W.J. Lindt, collection of the State Library of Victoria

Extract from Henry Gwynne’s will, Public Record Office Victoria, 45/918

Prize for A Social Experiment, ‘Women’s Work Exhibition’, Chronicle (Adelaide), 9 May 1908, p. 38

Examples of musical activities: ‘Lorne’, The Colac Herald, 14 August 1894, p. 3 and ‘Bendigonians at Lorne’, Bendigo Advertiser (Vic. : 1855 – 1918), 15 January 1897, p. 3

Review of The Mistress of Windfells, The Herald, 3 November 1921, p. 13

Agnes Gwynne’s signature, as it appears on the 1918 application for probate of Margaret Ann Sayers Gwynne’s 1909 will. Public Record Office Victoria, Wills and Probate, 158/144

Leave a comment