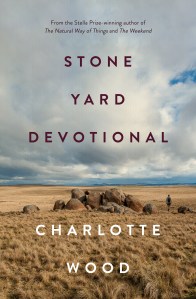

Stone Yard Devotional, Charlotte Wood’s seventh novel, takes the form of journal entries penned across several years. The journal is compiled by a woman who has left her marriage, her job, her friends, and her commitments to take up residence in an abbey on the Monaro plains in New South Wales.

Initially, the woman makes short visits to the abbey but, after several such brief stays, she simply remains there. For company, she has the abbey’s sisters, a plague of mice, and her past.

The dislocated nature of the journal, with its intermittent entries, allows space for the reader to wonder and ponder. Who is this woman? Why has she severed all connection with her previous life? What prompted her to choose life in the abbey – an atheist within a cloistered religious community?

Below I’ve listed more of the questions I found myself considering, both as I read Stone Yard Devotional and for some time after I finished Charlotte Wood’s book. The questions may be of use to book clubs; if so, feel free to share them.

Note: the journal writer/narrator in Wood’s story is unnamed. In places where I would normally use the narrator’s name, I have used capitalised versions of ‘She’ and ‘Her’.

‘What’s in a name?’ (Romeo and Juliet)

Charlotte Wood names the nuns (sisters Simone, Bonaventure, Josephine, Sissy and Carmel, novice Dolores, and the three elderly sisters who relocate to a Sydney nursing home) and the abbey’s visitors and temporary guests (including odd jobs man Richard and the visiting Sister Helen). But the narrator is not named and there is no clue as to her physical appearance – no hair or eye colour, no height or body shape, no reference to her clothing. (We can gauge her age to be around sixty.)

Questions

Do you think Wood had a name for her character and a clear picture of what She looked like? Did you form your own picture of her as you read? What would you name her?

‘A place entirely dedicated to silence’

‘In the church, a great restfulness comes over me. I try to think critically about what’s happening but I’m drenched in a weird tranquillity so deep it puts a stop to thought. Is it to do with being almost completely passive, yet still somehow participant? Or perhaps it’s simply owed to being somewhere so quiet; a place entirely dedicated to silence. In the contemporary world, this kind of stillness feels radical. Illicit.’

The silence is one of the first things She notices on her initial visit to the abbey. It is ‘so thick it makes me feel wealthy’, it’s ‘shockingly peaceful’. She quickly comes to appreciate that ‘the beauty of being here is largely the silence … Not having to explain, or endlessly converse.’

Questions

Opportunities for quietness and stillness are disappearing in a technologically connected world. Does the human experience suffer from this loss?

How might you feel about spending days, weeks or years in silence?

‘This work of transformed and even distorted memory’ (Sleepless Nights)

Charlotte Wood’s second epigraph reads: ‘This is what I have decided to do with my life just now. I will do this work of transformed and even distorted memory and lead this life, the one I am leading today.’ (Elizabeth Hardwick in Sleepless Nights, first published in 1979 when Hardwick was 63.)

As Her life at the abbey extends, episodes from childhood reach repeatedly for the surface – the actions of school teachers, the cruelties inflicted on ostracised pupils, the ways her parents contributed to the life of the rural community, the startling incidents that captured the attention of the townsfolk.

Questions

To what extent does being on the Monaro, the place of her childhood, influence the emergence of memories? Does the atmosphere of silence contribute to freeing long-forgotten events? Are physical space and psychological space equally important?

‘An incomplete unhurried emergence of understanding’

Describing her experience of Lectio Divina (Divine Reading), She writes: ‘The process is strangely beautiful. Sister Bonaventure says […] that if you remain troubled or confused by it, you just “hand it over to God”. This is so antithetical to everything I have believed (knowledge is power, question everything, take responsibility) that it feels almost wicked. The astonishing – suspect – simplicity of just … handing it over.’

A willingness to ‘hand it over’ is emblematic of monastic life. The narrator comes to appreciate and accept ‘an incomplete unhurried emergence of understanding, sitting with questions that are sometimes never answered.’ This ethos is the antithesis of the instant, often Googled, answers we demand today.

Questions

What is it about the rhythm of life at the abbey (participating in Lectio Divina, eating meals in silence, attending church services regulated by the Liturgical Hours, completing daily chores) that generates a willingness to sit with unanswered questions? How long might such a profound shift in attitude require before it takes hold in a person?

‘I’m eternally stuck … The fact of grief making itself known, again and again.’

She is a young woman, probably in her twenties when, first, her father and then, her mother die. At the beginning of Stone Yard Devotional, before arriving at the abbey for her initial stay, She stops in her childhood town and visits her parents’ graves ‘for the first time in thirty-five years’. She remembers the day she received a phone call telling her the headstones for the graves were ready. Everything within her plummeted, ‘like a sandbank collapsing inside me’.

Towards the end of Stone Yard Devotional, on an icy, wintery morning, She is sweeping the abbey courtyard. ‘As I swept it came to me that my inability to get over my parents’ deaths has been a source of lifelong shame to me. I used to think that time, adulthood, would clean it away, but no. It recedes sometimes but then returns and I’m eternally stuck; a lumbering, crying, self-pitying child. The fact of grief making itself known, again and again.’

Questions

Why is Her grief so deeply persistent, so much so that it makes her feel ‘eternally stuck’? Compare this with the description of her mother’s grief who, some years after Her father’s death, ‘slowly emerged, dignified and altered’ and then went about her life with ‘the calm authority I’ve seen sometimes in people who have endured great loss’.

How might it be possible for Her to become unstuck and emerge from her grief ‘dignified and altered’? Even if she becomes ‘unstuck’, is it the very nature of grief that it makes itself known ‘again and again’?

‘You know there are good books in those shelves, don’t you?’ (Sister Simone)

In the abbey’s sitting room, Sister Simone finds Her reading. The nun looks at the book in her hands and snorts: ‘You know there are good books in those shelves, don’t you?’ The narrator knows there are works by ‘Dorothy Lee, Edith Stein, Joan Chittister, Simone Weil, Ariel Burger. Arendt, Nussbaum, Hitchens, Robinson, Merton’ but Simone has caught her ‘engrossed in Stories of the Saints. A children’s book, I suppose – or, if not, a book compiled by or for a simpleton.’

Questions

What might have drawn Her to this book? What books would you have expected to find on the abbey’s shelves? Are you surprised see works by the American philosopher and converted-Jew Martha Nussbaum, and the British journalist and staunch atheist Christopher Hitchens included?

‘What does it take, to atone, inside yourself? To never be forgiven?’

Forgiveness, according to the Macquarie Dictionary, is an act of granting ‘free pardon’. Atonement is about making amends, it is ‘reparation for a wrong’.

Forgiveness is a choice, a decision of heart and mind, a relinquishing; atonement requires the generation of something. Amends need to be made.

During her primary school years, She heard stories of Catholic saints. She admits that the stories have left her ‘confused about the nature of forgiveness, and of atonement, and the conditions under which they could take place’. Much later, when she has become a permanent resident at the abbey, she reflects on the life of a young man from her town who murdered his parents. She wonders: ‘What does it take, to atone, inside yourself? To never be forgiven?’

Questions

Forgiveness is a theme that permeates Stone Yard Devotional. Does She need to forgive someone and, if so, why? Is she seeking forgiveness for herself?

Atonement is not a commonly used word in Australian secular life; it is usually confined to a religious context. Can you think of any modern acts of atonement that you’ve witnessed?

Writing the journal could be interpreted as an act of atonement. Do you think it would be an effective act? Are there other aspects of Her life at the abbey that could be interpreted as atoning?

Stone Yard Devotional

The word ‘devotional’ is an adjective – prayer might be described as a devotional activity. Equally, collecting eggs, sweeping paths, disposing of dead mice and peeling potatoes can all be devotional in intent. They are all acts of service.

Questions

The word ‘devotional’ does not appear anywhere in the text of Charlotte Wood’s book. What might be its meaning in the title? Why do you think Wood chose that particular word?

Further threads

The questions listed here touch on only some of the narrative threads that run through Stone Yard Devotional. Others include several juxtaposing ideas: the balance between perils and solace evident in small town life, the negligible impact of COVID on an enclosed community but the inescapable impact of the mouse plague, the daily frictions of living in a community (none of whose members have chosen each other) as opposed to the ongoing comfort of belonging, and the tension between action in the world versus living a cloistered life separate from it.

Charlotte Wood offers her readers much to ponder. There are no easy answers but there is no hurry. As the narrator’s mother might have said, all that is needed is time.

‘I shovelled the compost and spread it, shovelled and spread, preparing the soil and waiting for things to make sense. Tried to attend, very softly and quietly, which is the closest I can get or prayer.’

Links and sources

- Stone Yard Devotional by Charlotte Wood. Allen & Unwin. 2023. (All quotes, unless otherwise attributed, are from Stone Yard Devotional.)

- Charlotte Wood’s website

- Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare. Penguin. 2016.

- Sleepless Nights by Elizabeth Hardwick. Allen & Unwin. 2019.

- Macquarie Dictionary

- A simple description of Lectio Divina is available on the website of the Benedictine Abbey at Jamberoo, New South Wales. The abbey website also offers a glimpse into the life of an Australian female religious community, not unlike the one described by Charlotte Wood.

Image credits

- ‘Monaro 1’ by Ian Sanderson (2009) CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic

- ‘Monaro 2’ by Ian Sanderson (2015) CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic

Leave a comment